life in silence

M O N A S T I C P A G E S

1

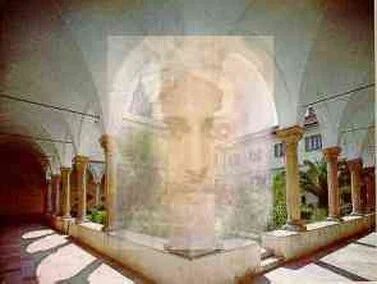

St. Mary's Abbey of Finalpia (SV)

In the cloister of every Abbey there is a garden.When God created man, he placed him in the garden, where he met his death. In a garden was the sepulchre from where He has risen to defeat death. In the ancient Persian language garden means heaven. A bit of heaven looks at on the garden of every cloister.

But even the spiritual reflection of the monks themselves is not the most important thing in the monastery. What is far more important still is that the Word of God comes silently into their midst, and eats and drinks with them, Divine Wisdom not only gives them wine to drink, but "takes His delight with the children of men."

It is because the monks enable one another to live most easily and peacefully in solitude and silence, because they provide for one another an atmosphere of recollection and solitude and prayer, that they are able to achieve the supreme end of the monastic life which is this spiritual and hidden banquet-the feast in which the Word sits down at table with His chosen ones and finds pleasure and consolation in their company. And He says: "I have come into my garden . . . I have eaten the honeycomb with my honey: I have drunk my wine with my milk: eat, O friends, and drink: be inebriated, O my dearly beloved" (Canticle 5:1)

The comunity has an essential part in the cenobitic life to develop the spiritual life of the monk but the monastic horizon is clearly the horizon of the desert. The monk, then, is one who has heard God speak the words He spoke once through the Prophet: "I am going to lure her and lead her out into wilderness and speak to her heart" (Hosea, 2).

His ears are attuned not to the echoes of the apostolate that storms the city of Babylon but to the silence of the far mountains on which the armies of God and the enemy confront one another in a mysterious battle, of which the battle in the world is only a pale reflection

The monastic Church is the Church of the wilderness; the woman who has fled into the desert from the dragon that seeks to devour the infant Word. She is the Church who, by her silence, nourishes and protects the seed of the Gospel that is sown by the Apostles in the hearts of the faithful. She is the Church who, by her prayer, gains strength for the Apostles themselves, so often harassed by the monster. The Monastic Church is the one who flees to a special place prepared for her by God in the wilderness, and hides her face in the Mystery of the divine silence, and prays while the great battle is being fought between earth and heaven.

Her flight is not an evasion. If the monk were able to understand what goes on inside him, he would be able to say how well he knows that the battle is being fought in his own heart.

The desert that during the Exodus the Jewish people had to face, before reaching the Promised Land, was like the image that we see here, Sin desert.

It's not in fact a sea of dunes of sand, like they are seen in the Sahara desert, but of a alternating relief and tablelands that the periodic rains covered with luxuriant pastures, but also precarious. That's why the people could have carried with themselves a great quantity of livestock.

But we nave also come to understand that the peace of the monastic life is not a material peace, not a state of comfortable inertia, guaranteed by the absence of all cares and responsibilities. Concerning a peace which gratifies the body rather than the soul, Christ said only that He came to bring "not peace but the sword (Matt. 10: 34).

The peace of the monk is proportionate to his detachment from the things of earth. It is the peace not of one who finds all his earthly desires and needs taken care of in a satisfactory manner, but of one who, to some extent , has become independent of material things by concentrating his whole life on a search for the Kingdom of God. God. To enter the Kingdom of God it means to realize that God takes care of me with affection and fatherly interest and that, done sincerely my part, it is normal that I abandon myself totally in Him.

He is free, with the liberty of the sons of God. His peace is not of this world. It is hidden with Christ in God.

The monastic life is the more hidden in proportion as it is humble, solitary and poor. The monastic spirit is above all a spirit of solitude, of separation from the world. The monk is by nature alienated from the apostolic ministry of preaching, as well as from prelacies and dignities that would keep him before the eyes of men. If he is, like the Apostles, a "spectacle to angels and to men" it can only be as an example of poverty from which the world tends to turn away without understanding. Consequently, every monk has in his heart the aspiration for an ever-greater solitude, and poverty and humility. If the dispositions of divine Providence may involve him, for a time, in work that places him before the public, he knows that this disposition is purely accidental, and that the essence of his vocation remains the same: it is always a call to solitude, to self-renunciation.

It is a call to the desert.

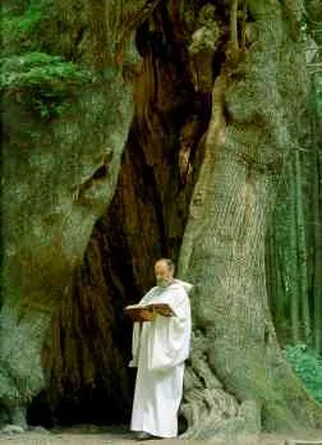

The desert and the solitude are also found in the silence of the forest.

A stretch of the Jordan River

The whole day of silent adoration of who knows how to plunge himself habitually in his inner life prolongs his Mass and his Eucharistic Communion, maintains him constantly in the most intimate relationship with God by means of a faith so pure and a charity so ardent that they don't find comparison in any other form of life. Who habitually cultivate his inner life, lives like buried [plunged in] in hope, with his mind and his heart stretched out from this world, toward the Father. Always on the threshold of eternity, he fixes his eyes on the eschatological obscurity of the future and he fills his lungs of pure air of the World to come. The purity of his faith, of his hope, of his love is essential to the life of the mystical organism of the Church, and we all draw big profit from it.

... And the joy of the hermit-monk in his vocation of pure solitude and renunciation is a river which goes forth, through the secret channels of the Communion of Saints, to make glad the city of God and strengthen the arms of those who labor and fight for God in the market places of distant cities. This heightened sense of unity in Christ is also the source of the hermit's "Eucharistic" spirit and the fountain head of his thanksgiving. Even though in his solitude he may have moments of terrible darkness and isolation, even though his sense of his own poverty and aloness before God, may grow as the years go on, the hermit, never loses his deep sense of supernatural solidarity with the whole Mystical Body of Christ.

Why should he? Unlike the Apostle, who is often bewildered and blinded by the confusion that surrounds him at all times, the monk may, by the gift of God, come to a deep realization of the fact that he is present by his prayers and by his charity in the hearts of men whom he will never see on earth. He will be obscurely reassured of the fruitfulness of his hidden apostolate which is all the more effective for being uniquely and integrally supernatural pure product of theological virtue, and of prayer directed by the Holy Ghost.

All that the monk does should promote that puritas cordis which makes contemplative union possible. The two great means to this end are silence and meditation. Both, are vitally important. Neither one is of any avail without the other. "For silence without meditation is death, it is like a man buried alive. But meditation without silence is pure frustration - it is like the struggling of the man buried alive, in his sepulchre. But both silence and meditation together bring great rest to the soul and lead it to perfect contemplation."

The silence that is required for this interior meditation is first of all a silence of the tongue, a silence of the body, a silence of the heart. The tongue renounces useless and evil speaking. The body is silent when it abandons useless and harmful actions. The heart is silent when it is purified from useless and evil thoughts. For what would be the use of keeping silence with your tongue, if you have tumult of vices raising a storm in your actions and in your mind ? The purpose of this silence is not merely negative. It has a positive and constructive force in the life of prayer. It is indeed one of the best and most efficacious of ascetic weapons because it is one of the most positive. Silence builds the life of prayer which, like the Temple of Solomon, is an edifice which must grow without the sound of any iron tool. "The house of God grows in sacred silence, and a temple that will never fall is constructed without noises." And the legislator goes on: If you are quiet and humble, you will not fear what your flesh may do to you. For where the Heavenly Dweller rests in peace, the betrayer cannot prevail." It is in the silent soul that wisdom takes up her abode, and remains forever. (In silenti, et quiescenti vel meditanti anima permanet sapientia.)

...just as St. Anthony of the Desert placed discretion at the top of his list of virtues, as being the mother of them all, so too the monk will learn to live in a spirit of sobriety and moderation. The sobrietas we here consider is too big to be fitted into the narrow limits of a scholastic category. It overflows the bounds of temperance and includes prudence and justice and fortitude. Like Benedictine humility, it is really an integrated organism of good habits which governs and orders all our actions in reference to their proper end.

... Pietas is a kind of disposition of heart which, with merciful tenderness, is patient and sympathizes with the weakness of other men; monks should be human, patient , merciful and meek...

Chartreuse of Pavia Church's interior

A modern highway at dawn.

(Today, man runs the risk of not expressing anymore his unique and irreplaceable message, but to slide away - anonymous - in time).

The world of men has forgotten the joys of silence, the peace of solitude which is necessary, to some extent, for the fullness of human living. Not all men are called to be hermits, but all men need enough silence and solitude in their lives to enable the deep inner voice of their own true self to be heard at least occasionally. When that inner voice is not heard, when man cannot attain to the spiritual peace that comes from being perfectly at one with his own true self, his life is always miserable and exhausting. For he cannot go on happily for long unless he is in contact with the springs of spiritual life which are hidden in the depths of his own soul. If man is constantly exiled from his own home, locked out of his own spiritual solitude, he ceases to be a true person. He no longer lives as a man. He is not even a healthy animal. He becomes a kind of automaton, living without joy because he has lost all spontaneity. He is no longer moved from within, but only from outside himself. He no longer makes decisions for himself, he lets them be made for him. He no longer acts upon the outside world, but lets it act upon him. He is propelled through life by a series of collisions with outside forces. His is no longer the life of a human being, but the existence of a sentient billiard ball, a being without purpose and without any deeply valid response to reality.

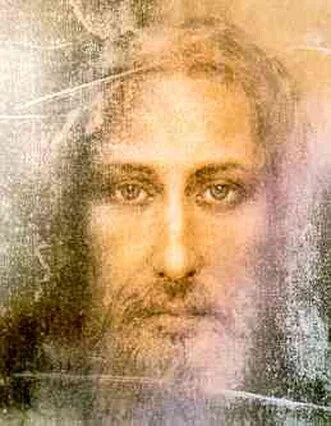

The Holy Shroud's face elaborated by NASA's computers.

But in proposing to the world the sanctity of the monastic life as an example, the Church does not merely seek to humiliate and reproach sinners. In fact, that is never her attitude. She is a kind mother. Her authority seeks to develop men to help them grow and seek happiness, not merely to punish them and reprove them and take away even the last ounces of vitality and joy, which they still retain in their souls. The monastic life is therefore always a witness to the joy and vitality and fruitfulness of the life of the Church. It is in this sense above all that monasticism will always manifest the Church's inexhaustible reservoirs of sanctity. For sanctity and life are one: holiness is the special value of the life that comes to man's soul direct from God. Holiness is life lived in its fullness, in union with the Living God. Life brings to perfection all the deepest resources of man's nature, before elevating him to the perfection of supernatural and mystical union.

Just as Moses in the solitude of Mount Horeb led his flocks into the inner parts of the desert, and there saw the burning bush, and heard the Voice that spoke, and learned, from the Voice, the unutterable and Holy Name of God, so too the monk penetrates into the wilderness by silence and perfect solitude. There he discovers the "burning bush" which is his own spirit, enkindled with the fire of God but not consumed... God is the Living God, burning like an intangible flame within the substance of our own spirit that derives all its life from Him.

The Flame of God is the Flame of pure life, infinite Being, Absolute Reality. Only those know Him who have themselves abandoned all falsity and all illusion and all pretense and all sham. More than that, they have abandoned themselves, they have ascended above themselves, they are beyond themselves. And in rising beyond themselves, they have become most perfectly themselves, no longer in themselves but in Him.

The voice they hear is no longer the voice of a philosophical intuition, no longer the echo of the words of divine revelation, but the very substance of reality itself - Realty not as a concept, but as a Person.

And thou, whoever thou art, who livest in solitude, and leadest a solitary life having led thy flocks, that is to say thy simple thoughts and thy humble affections, into the depths of thy loving will, there thou wilt find the bush of thy humility, which heretofore brought forth nothing but thorns and briars, radiant with the light of God. For thou wilt be glorifying and bearing God in thy own body. This is the divine fire which enlightens as without burning us, gives radiance but does not consume us. . . . And the bush that burns without being consumed is human nature enkindled with the fire of divine love, and unharmed by the slightest touch of destruction.

(Excerpt from a writing by Thomas Merton)